by Bruno Di Tillo

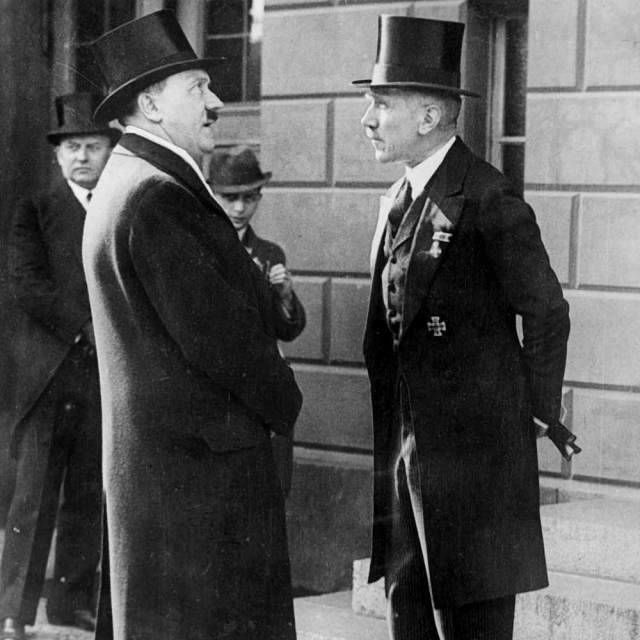

By 1933 Nazi support in the Reichstag was becoming skimmer, and the electorate of the Party as a whole was moving towards other coalitions. In November 1932 Nazis had 33.1% of the Reichstag seats and had lost 34 seats from the 230 of the July elections[1]. Hindenburg had won the second and final April election of 1932; he’d surpassed Hitler by a mere 16.2% percent[2], but in the meantime he’d lost the Centre and most of the Conservative right; his political supporters had been shifted with the last election from the old militarist guard of the far-right to the Social Democrats’ coalition that now supported him in fear of Adolf Hitler’s rise, thus seeing Hindenburg as the lesser evil[3]. Bruening’s presidential government experiment had drawn most of the conservative elites and some of the industrialists [4]towards a more authoritarian government. In the meantime, German economy was declining because of the heavy sanctions brought onto by the Versailles Treaty of 1919 and as a result of the worsening of the Wall Street Crash of ‘29. In July 1930 the unemployed population had risen to 14.4%, to then reach its peak 52.4% in 1933[5]. By late 1930, the NSDAP had made a huge leap forward from 1928’s 12 seats in the Reichstag to 107 [6]. In the July election of 1932 Hitler’s demand for chancellorship was met by Hindenburg with a complete denial. In his place, the President of the Weimar republic appointed Franz von Papen, who stayed in power until December of the same year, in a coalition with the Nazis. In the November elections Hitler, backed up by the Nazis’ 196 seats in the Reichstag, repeated the task of asking Hindenburg for his installation, but was again rejected in favor of Papen. On the same occasion, Kurt von Schleicher, head of the army and a close advisor of Hindenburg firstly broke his coalition with Papen’s government to then ask the chancellorship for himself. The request was denied in November, but was later reluctantly picked up by Hindenburg following the fall of Papen’s government. On the 4th of January Von Schleicher’s weakening support in the Reichstag brought Papen to formally disregard his forced coalition with Schleicher in favor of working for Hitler. On the 22nd Von Papen request for Hitler’s installation as chancellor was refused; following Schleicher’s resignation on the 28th, Hindenburg found himself to want Papen back as chancellor, but in the end appointed Hitler on the 30th. The Centre Party, previously in a fragile coalition with Bruening, decided to support later on the Nazi-driven government in the belief that Hitler would’ve been an easy adversary to keep at bay[7].

_——————————————————————–_

FRANZ VON PAPEN’S MEMOIRS

Franz Von Papen, Memoirs, trans. Brian Connell. London: Andre Deutsch Limited, 1952

This book, written by Papen and translated by Connell in 1952, elucidates upon the events spanning from the early years of the republic to the end of the Nuremberg trials. A substantial part of the book covers Papen’s personal intromissions in the last days of the Weimar Republic and his role in Hitler’s rise. The book offers insights from a member of the transitional government of 1933 and gives the reader a detailed overview of Papen’s person viewpoint over the matters of the Nazis’ ruling. This value is also its greatest limitation; being written after the Nuremberg trials where Papen had been lifted of all charges, it presents itself as a possibly biased resource that could’ve been crafted as a way to legitimize Papen’s own innocence and thus being held for account of international authorities. Thus at this point one could say that the Memoirs have two possible purposes: the first being a personal elucidation of the instability of Germany’s politics in the Weimar-Nazi period; the second being a textual analysis crafted to exonerate Papen from the international accusations of favoring and aiding voluntarily the rise and installation of Adolf Hitler.

————————————————————————-

Papen writes: “most of the political parties had been prepared at one time or another during 1932 to consider a Cabinet with Hitler as Chancellor”[8]. This statement has to be assessed in terms of the known facts; in the November elections of 1932 it is true that Hitler had lost by about 16% votes for Presidential elections, but the seats lost in the Reichstag by the party during that same period could translate in a loss of power. Papen, though, sees this as an affirmation of control by Hitler[9]. By December of the same year, Strasser, having been offered by Schleicher the position of Vice-Chancellor and PM of Prussia and seeing Hitler’s open dictatorial ambitions as the one thing that would’ve kept the Party away from position of power, had drifted away from the Party without any major Nazi members. According to Papen’s point of view[10], Hitler had stood up in front of this with such ruthlessness, that he deems it exaggerated to assert that his control over his Party was anything but a stranglehold. It could be hypothesized that the reason why in January Hitler did get appointed was because of this control that the Weimar system lacked and that Hindenburg valued over the new democratic model of the country. The evidence would suggest that Hitler’s installation was not accompanied by a political setting that could’ve aided Hitler had he decided to try a new coup d’état; this could mean that the reason why he came to the position of chancellorship must reside in the intromission of a strong political figure.

This political figure could not be Hindenburg himself, as most sources, namely Shirer[11] and Larry Eugene Jones, who sees in Papen the true cause of Hitler’s chancellorship[12], refer to him as a senile puppet in the hands of his advisers. In Birdshall’s book review, it is stated how Andreas Dorpalen suggests that Hindenburg, throughout his political career, “was a man marked by indecision and by a reluctance to accept responsibility”[13]. Furthermore, Dorpalen adds that it was because of what he calls lethargy to action and his increasing dependence towards four advisers, namely Papen, Schleicher, Meissner, and Oskar von Hindenburg, that he came to the conclusion that Hitler’s candidacy had to be taken seriously. Papen would be proving this partially correct, as he states that Hindenburg did not see Hitler’s installation as an actual solution until the last days before the official installation, but had seen that at least a coalition with the Nazis was necessary[14].

This would prove true, considering that Hindenburg had asked Hitler to join a coalition government with Schleicher, which the future dictator refused asking for full powers. Papen also points out how, according to his introspections, it was Schleicher’s decision to present the resignation of his Cabinet in 1933 that pushed Hindenburg to see Hitler as a possible candidate[15]. Schleicher’s position in the Reichstag posed a threat to Hindenburg himself, and the rumors[16] about his plans on a Reichswehr Putsch to seize the presidency that followed his last days in office added on to his dislike. Papen also states that the threat that Hitler posed to Hindenburg on the 30th of January 1933 about new Reichstag elections might have aided his consolidation of the power given to him[17]. Petzold, though, sees in Papen the direct cause of Hitler’s chancellorship, and not an effect of his power over the Reichstag[18]; Petzold states that Papen, backed by leading Ruhr industrialists that had secretly supported the November 1932 petition for Hitler’s chancellorship, had been fully aware of Hitler’s imprimatur by said industrialists, and thus crafted his way out in order to create a coalition with him and have a favorable hand with key industrialists.

Papen, though, states in his memoirs how Hitler was brought to power with the belief that in a brief period a possible parliamentary majority would have been created to counterbalance his power and thus control Hitler’s decisions[19]. This viewpoint counterclaims the fact that the purpose of Papen’s involvement with Hitler was brought onto by industrialist goals because it would show Papen’s loyalty towards the democratic system. An objection should be made about both points. If it is true that Papen was aiding the democratic system by pushing Hitler’s candidacy, then [name] point that other coalitions could’ve been crafted out of the unstable social situation should be used as a counterclaim for both.

Wormuth[20] offers an interesting point, stating how Hitler’s rise had not been the result of Papen’s machinations within Hindenburg, but much rather a casual beneficiary of the deadlock that had been the fall of the middle class following the depression, as the Nazi movement had been kept alive by the worsening of the social situation[21]. Although, Shirer sees Papen as an incompetent figure in the Reichstag’s political system, but still sees that he was eager enough to aid Hitler following his failed attempt as chancellor as the future dictator would grant him a position in his new Cabinet.

It should also be stated that although Hindenburg did not trust Hitler, he trusted Papen enough to keep him at bay as he would appoint Hitler on the condition that Papen would be part of his official Cabinet. Whilst this might be a reason why Papen could’ve wanted Hitler in power as it would’ve granted him the post of vice-chancellor, a phrase he stated in 1933 could ultimately prove that he did not favor Adolf Hitler’s position, but merely desired to control the situation and re-insert himself in a position of power: “Within two months we will have pushed Hitler so far in the corner that he’ll squeak”[22].

While it remains unclear why Papen decided to side Hitler, it is obvious that the reasons must reside in the thirst for power of both politicians. While Hitler did not have the numbers to either take on a violent revolution, he did have the political leverage to take onto the Reichstag by going to the polls after December 1932. While it remains obvious that Hindenburg had no real power anymore as he relied on counselors and was threatened by the possibility of new elections, Papen’s decision to back the Nazis can thus be seen as a way to either control Hitler to then push him out of the governmental institutions to then restore the power to the Reichstag, or conversely a way to gain power for himself and ultimately create a new coalition government with him as chancellor. Granted that Hindenburg himself was ultimately trusting Papen, it is possible to say that it was him and not Hitler to manipulate the senile nature of the president and thus was the head of Hitler’s chancellorship.

CITED WORKS

- [1] p.22 Documents and debates-20th century Europe. Richard Brown and Christopher Daniels

- [2] The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. p.159. William L. Shirer

- [3] Themes in Modern European History- Paul Hayes p.187

- [4] seminar studies in history:the third reich, DG Williamson p-6

- [5] p-407 Bruno frey……. political behavior

- [6] themes in modern european history-paul heyes

- [7] seminar studies in history:the third reich, DG Williamson p-6

- [8] Papen, memoirs. 226

- [9] Papen, memoirs, 227

- [10] Papen memoirs 227

- [11] Shirer, The Rise and fall of the Third Reich

- [12] Larry Eugene Jones,

- [13] Review by Birdshall S. Viualt Andreas Dorpalen. Hindenburg and the Weimar Republic 506

- [14] Papen memoirs, 235

- [15] Papen memoirs, 238

- [16] Papen memoirs, 243

- [17] IBID

- [18] German Studies Larry Eugene Jones 143-144

- [19] Papen 244

- [20] Wormuth, the responsibility for Hitler 681-2

- [21] Wormuth, the responsibility for hitler 681-2

- [22] Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947, p.